The moment everything changed

Two weeks after this photo was taken, I almost died.

I survived a ruptured cerebral aneurysm, which led to a subarachnoid hemorrhage—or in simpler terms, a life-threatening brain bleed.

One year later, my body has fully healed, and I’m deeply grateful to be alive. Yet the mental and emotional pain lingers, a quiet battle that continues long after my physical recovery.

This is my story.

I was getting ready to head to Cincinnati for a wedding when a searing bolt of pain struck my head like lightning splitting the sky. The pain struck without warning—sudden, blinding, and utterly unbearable. I typically have a high tolerance for pain, but this was unlike anything I’d ever felt.

It brought me straight to my knees, sobbing uncontrollably. My neck stiffened, my vision blurred, I saw flashes of light, and there was a ringing in my ear. I felt the nausea creeping in and crawled to the bathroom, barely able to hold myself up. I took a couple deep breaths and waited for the pain to subside, but it never did. It kept getting worse, coming in waves that kept crashing into my head.

I was alone.

My husband was mid-flight from a work trip. My three kids were at school. I tried texting my husband, but the messages went undelivered—just those dreaded green bubbles. That’s when the fear hit me. Deep, visceral, and paralyzing.

I thought, Is this how it’s really going to end? Am I going to die here, alone?

I couldn’t let my kids or my husband find me like this. I swallowed the panic and forced myself to stay calm. I didn’t have the luxury of losing control.

I called my good friend, an ER doctor, and described my symptoms. He didn’t hesitate. He gave me his differential diagnosis, trying to reassure me it was probably nothing life-threatening, but better to be safe and get checked.

“It’s most likely a very severe migraine, but there is a small chance it could be viral meningitis or a brain bleed. They’ll need to run some scans and tests to be absolutely sure. Whatever it is, you need emergency medical attention. Get to the ER right now. It would be perfectly appropriate to call 911 if you can’t drive.” He didn’t want me to worry, but his tone told me enough.

Looking back, that moment has replayed in my head countless times. People often ask why I didn’t call 911 right away, and to be honest, it just felt too dramatic at the time. I was still conscious, still moving, and couldn’t believe it was that serious. I didn’t want the attention—the flashing lights, the neighbors watching, the spectacle of it all. It seemed excessive, even embarrassing.

“Am I going to die?”

My voice cracked and trembled.

I could barely swallow past the tears.

“I’m really, really scared.”

He wasn’t sure but he didn’t want me to panic. He tried to sound calm, steady. As an ER doctor, he’s used to being direct, to telling the truth no matter how hard it is, but this was different. I wasn’t just another patient. I was his friend.

“You’re going to be okay,” he said. “If it were going to happen, it already would have.”

At the time, he was just trying to keep me calm. The moment I told him, “This is the worst headache of my life, and it came out of nowhere,” he knew something was seriously wrong—but he stayed steady so I wouldn’t panic. Only later did I realize how much he’d been holding back. When we talked about it afterward, he admitted he had known it was very serious but didn’t want to show it. “You’re never dramatic,” he told me. “But I could hear the pain and fear in your voice.”

His words echoed in my head, sharp and unreal. My vision was narrowing, but I kept going. I texted my friend, the one I was supposed to drive to the wedding with, and told her there was a change of plans. Instead of going to Cincinnati, I needed her to drive me to the ER.

My hands were shaking as I texted our babysitter to pick up the kids after school and take them to my parents’ house. There was no need to worry them yet. They already thought I was leaving for the weekend. The pain pulsed behind my eyes, a crushing throb that made it hard to think. Still, I kept texting with friends and family, kept coordinating, because even as my body was shutting down, something in me refused to let go of control.

When I arrived at Dublin Methodist Emergency Room, the nurse asked what was wrong, and I just started sobbing. I couldn’t speak, so I held up my phone and let her read what I had typed. They took me back immediately and started an IV. Morphine did absolutely nothing for the pain.

The room spun and blurred, voices rising and fading around me. Footsteps drifted in and out of the haze — sharp, distant, then suddenly close. Of all things, I found myself apologizing — for ruining the weekend, for missing the wedding, for being a bother, for letting anyone down. Maybe it’s from years of being a people pleaser, but even then I was more worried about being a burden than about what was happening to me.

They ran blood tests and ordered a CT scan.

I remember the moment the doctor came in, somber, and told me quietly, “You have a brain bleed. You’re going to need emergency brain surgery.”

In that moment, the life I once knew vanished, and something raw, uncertain, and unrecognizable began.

I tried texting my husband again. Still green.

When his plane finally landed, he said his phone lit up with a barrage of messages from me; something that almost never happens. Later, he told me he read in three minutes what I had sent over a period of three hours, each message escalating in panic and fear.

The first said, “I don’t feel right.” The next, “I’m heading to the ER.” The last one: “They found a brain bleed.” Somewhere in between, I told him, “I’m really scared,” and, “I’m in so much pain,” words he almost never hears from me.

I can only imagine the dread that hit him in that instant, racing through the airport, trying to reach me, piecing everything together from miles away. It took everything in him to hold back tears as he rushed to get to me as fast as he could, carrying the quiet ache of knowing I’d been scared and he hadn’t been there to comfort me. For him, it wasn’t just fear; it was the helplessness of understanding too much and being too far away to do anything. As a trained neuroscientist, he knew exactly what “brain bleed” could mean. Still, amid the panic, he found a small measure of comfort in knowing that I hadn’t lost consciousness and was still able to text and communicate.

I was transported by ambulance to Riverside Hospital. At some point, I must have drifted off, because when I opened my eyes, my husband was sitting beside me, his face etched with quiet devastation. Looking at me, he didn’t need to ask. He understood all too well the seriousness of my condition. He signed the consent forms, and soon after, I was placed under anesthesia for surgery.

From this point on, everything becomes a blur. I remember drifting in and out of consciousness, fighting to wake up through the haze of heavy sedation. My arms were restrained—to keep me from accidentally pulling out the IVs—and there was something lodged deep in my throat. Later, I would learn it was a ventilator. I tried to speak, but no sound came out. My throat burned with rawness. I felt disoriented, helpless—trapped inside a body that wouldn’t cooperate. I was aware enough to know I was struggling, but too weak to do anything about it.

Eventually, I came to.

Through foggy eyes, I looked for my husband. My eyelids fluttered, adjusting slowly to the light. He was sitting to my left, looking utterly worn down—his face shadowed by grief and fear, his posture heavy with exhaustion.

I managed to croak out a faint “hi.”

His eyes widened, then lit up with a mixture of relief and disbelief.

“I have a wedding I need to go to,” I murmured.

He gave a small, wry smile and gently said,

“Today is Monday. The wedding was Friday.”

Three days had passed. I had no memory of any of them.

The neurologist came in and started asking questions. “What’s your name? What’s your date of birth? Do you know where you are? What day is it?” Then came the physical tests: “Squeeze my hands. Push up. Push down. Wiggle your toes.” I answered and followed each command without issue. I was confused—these were such simple questions. I didn’t realize this was going to be my new normal, every hour, for the next 19 days in the ICU.

At one point, I reached up to scratch my head and was gently stopped.

“Don’t touch the drain,” the nurse said softly.

“The drain?” I asked, confused.

That’s when I knew something was different. I lifted my hand to my head, and as my fingers moved across my scalp, they met short, coarse bristles where my hair used to be. My long hair was gone. Then I felt it—a small tube protruding from the front portion of my skull, right where the bleeding had been.

I hadn’t known it was there. In that moment, the reality of what my body had been through began to settle in. It was disorienting, like waking up in someone else’s life and I felt a wave of helplessness I couldn’t quite name.

Days and nights blurred together. It felt like one long, never-ending day filled with blood draws, shots in my stomach, neurological tests, CT scans, ultrasounds, and dressing changes. I lost all sense of time; everything just blended into the next procedure.

A couple of days later, the physical therapist asked if I could walk down the hallway. I didn’t think much of it. Walking came easily enough. My legs were steady, though I tired quickly. Still, just being upright again, moving under my own strength, felt strangely significant.

I didn’t realize then how big of a deal it was. To me, it was just walking. But to the doctors and nurses, it meant something more, that my body was recovering, or maybe that things weren’t as bad as they had feared. Every small step, every slow lap down that hallway, marked quiet progress, milestones I didn’t even know I was hitting.

When the catheter was removed, I had to call the attending nurse every time I needed to use the bathroom so they could disconnect the tubes and close the drain from my head. Eventually, I was doing most of it myself. The running joke became that I would answer all the questions and perform the neuro tests before they even asked. I was lucky. And I knew it.

Across the hall, a different story was unfolding. An older patient occupied that room, and I watched as his visitors would emerge in tears, their faces full of grief. Then, one day, the room stood empty and silent. I didn’t need to ask. I already knew. He hadn’t been as lucky as I was. That quiet void in his room haunted me. It reminded me that not everyone walks out of these situations. That surviving isn’t guaranteed.

And not long after, I learned of someone close to me—much younger—whose story also has stayed with me. She’s a young woman in her early thirties who suffered a ruptured aneurysm following pre-eclampsia after childbirth. Her recovery has been heartbreaking. She cannot speak. She struggles to walk. And she’s now trying to care for a newborn and 3-year-old while navigating a long, uncertain road back to herself.

The contrast between our paths is something I carry with me every day. We both faced something rare, sudden, and life-threatening. But while I was able to walk away with few visible signs, she is still deep in the hardest part of her fight. And like the man across the hall, she reminds me that recovery is not one singular story—it unfolds differently in everybody. I realize how easily that could have been me. And that reality never leaves me.

Over time, my husband filled in the blanks. Before I went into surgery, he was cautiously optimistic. I was still coherent, still myself, and he knew that any major damage would likely have already shown at that point.

The surgery was an emergency, risky by nature, but expected to be relatively straightforward. The surgeon said it should take about an hour to place a coil in the aneurysm to prevent it from rupturing again.

Instead, the procedure took nearly four hours. What was supposed to be routine quickly turned into a fight for my life. During the operation, I suffered a secondary bleed from a perforated vessel. I stopped breathing multiple times. By every measure, I should have died. The outlook was grim and bleak. What was meant to be a simple, hour-long procedure became a life-threatening ordeal that no one could have anticipated. I was placed on life support.

After the surgery, the neurosurgeon took my husband aside. He explained the complications, the unexpected bleeding, the moments they almost lost me. He told him words no one is ever prepared to hear: I might not survive. And if I did, I might never speak or walk again. I could be left permanently disabled.

“The person who wakes up — IF she wakes up,” he warned quietly, “may not be the person you remember.”

I can’t begin to imagine what it was like for my husband to hear those words. To stand there as the reality sank in, watching the person he loved reduced to a fragile, motionless body. I was surrounded by tubes, wires, and machines that were keeping me alive. While I lay unconscious, caught somewhere between life and death, he carried that unbearable weight alone. Just hours earlier, he had clung to a fragile sense of hope, reassured by my coherence and the surgeon’s confidence—never suspecting how quickly everything would change.

And yet, against all odds, every part of me, every cell, every breath, every heartbeat kept fighting to stay alive. My husband later told me he had never seen anyone fight so hard, even when my chances of survival didn’t look promising.

When I woke up—speaking, walking, working—everyone was in disbelief. My doctor called me a medical marvel. My husband could not comprehend how I was back to “business as usual.” I was messaging friends and family, running payroll from my hospital bed, refusing to let anyone down.

Looking back, I realize I was still trying to be the dependable one, the fixer, the people pleaser. Even from that hospital bed, I was desperate to prove I was still me. That the person who woke up was the same one who had gone under. It wasn’t just about work; it was about reclaiming something fragile, something I was terrified might have been lost.

Emotionally I was all over the place, grateful to be alive but also belligerent, paranoid, and deeply depressed. I felt upset about what had happened, and unfortunately my husband bore the brunt of that frustration.

At one point I became convinced someone at the hospital was trying to kill me. I remember thinking I heard someone breathing beside me in my room, even though I was alone. The sound was so vivid, so close, it made my skin crawl. I even called my husband to tell him that if I died, it would be because someone killed me.

Later I learned those intense feelings of paranoia and rage were side effects of an anti-seizure medication, Keppra, what some people called going “Keppra crazy” or “Keppra rage.” Still, the sense of betrayal ran deep, not just from my body but from a world that suddenly felt unfamiliar and unsafe.

The statistics were terrifying. Many people with this kind of brain bleed don’t survive, and those who do often face major deficits. Yet somehow, I ended up in the small percentage who walked away almost untouched. Almost.

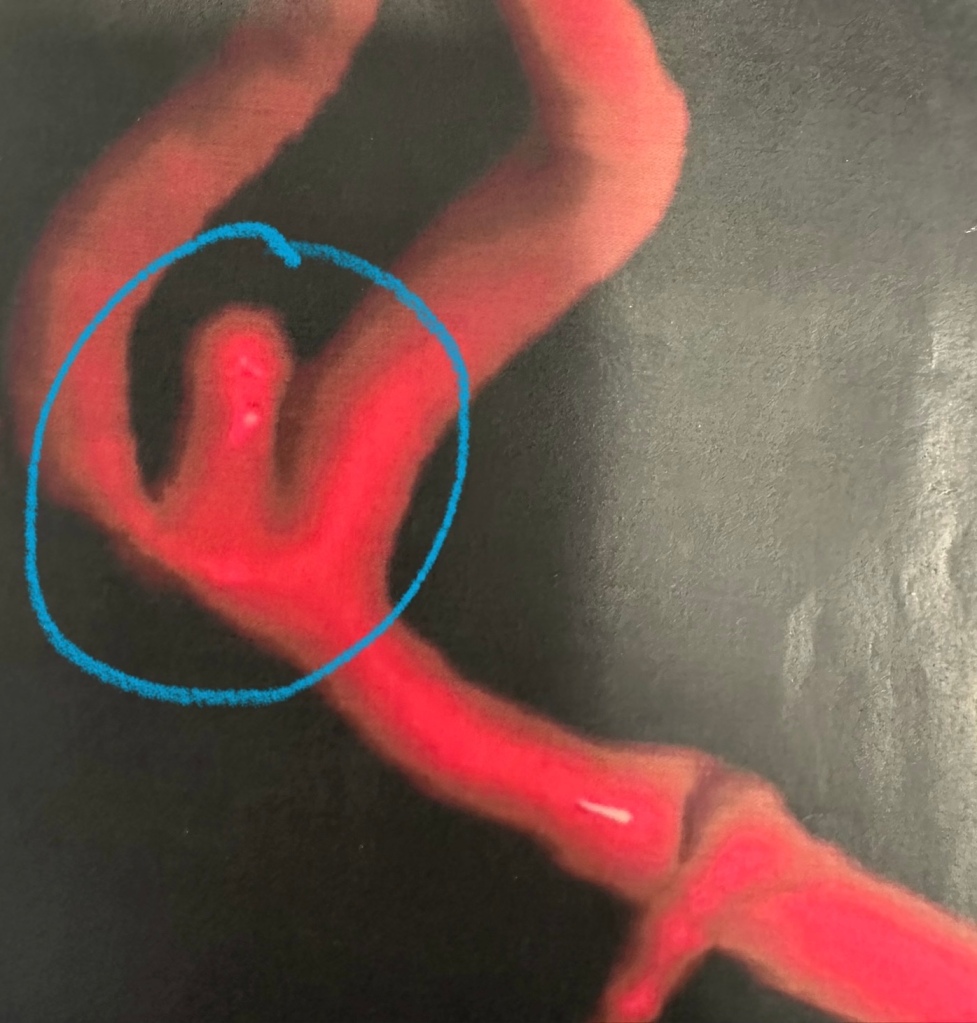

Now every six months, I have to undergo a cerebral angiogram—a procedure where a catheter is threaded through my femoral artery in my groin and guided up to the arteries in my neck. It’s how my doctors monitor the aneurysm in my brain, checking to see if it’s changed or grown. It’s not a routine anyone chooses. It’s invasive, uncomfortable, and each time, it reminds me how close I’ve come to dying.

After the rupture, everything feels different. Now, every headache sends me spiraling into fear and anxiety—wondering if this is just tension or the beginning of something far worse. Living with this kind of uncertainty is exhausting. You start to question every little sensation. But at the same time, this is the reality that’s keeping me alive. These check-ins, as terrifying as they can be, are also the reason I’m still here. And I try to remind myself of that when the fear creeps in.

I’ve learned to lean on humor—not because any of this is funny, but because sometimes laughter is the only thing that keeps me from breaking. I joked with the nurses that the aneurysm was worse than childbirth, and all I got was a bad haircut. It was a small joke, but in those moments, it made us all laugh.

I know it sounds strange, but I carry a deep, lingering guilt for having recovered so well when others haven’t, and for all that I put my loved ones through along the way. I still do.

My feelings are complicated. I’ve gone over it so many times. Why me? Why was I the one who came out of it unscathed? What does all this mean? What am I here for?

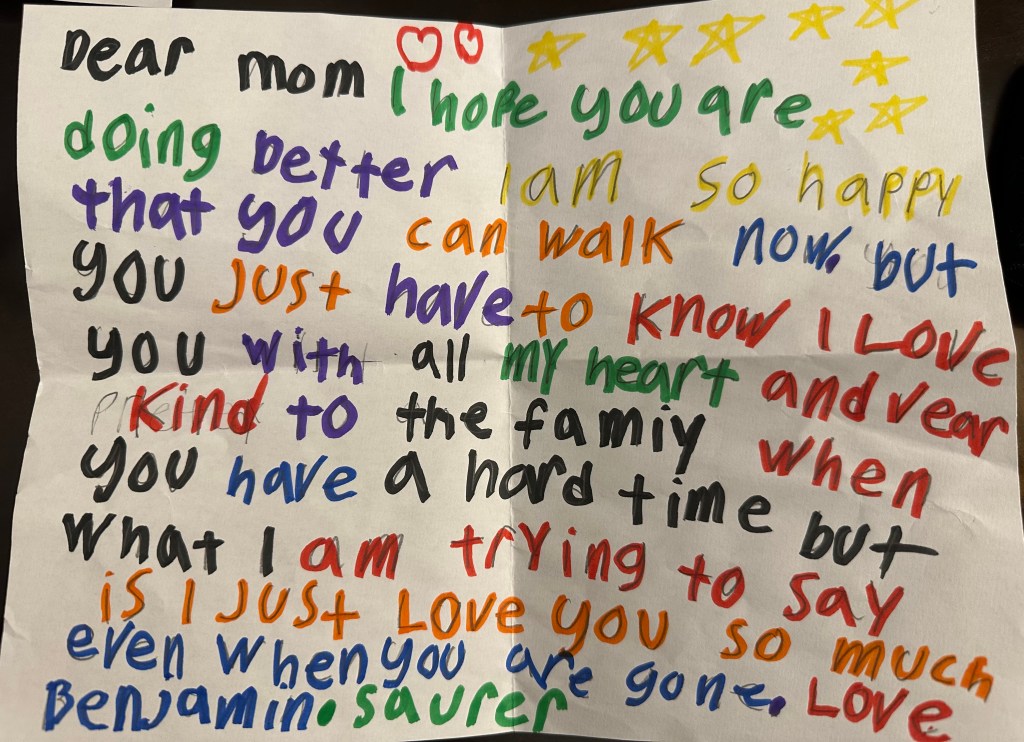

While I know none of it was my fault, I can’t shake the sadness and guilt for what my family and friends endured, especially my children. My kids have always seen me as superwoman, but in that hospital bed they saw me as human, fragile, breakable, and still fighting. Maybe that moment, as painful as it was, made me more real to them. I think about what that must have been like, seeing me with my head partly shaven, tubes coming out of my arms and skull, and I wonder what memories that left behind.

What makes it harder is that there was no reason for it, no warning sign, no pattern to explain why it happened. I live a healthy lifestyle. I don’t have high blood pressure. No family history. I wasn’t stressed or doing anything strenuous the moment it happened.

When I asked the doctor, he said, “We don’t know…you’re just unlucky.” I hated that answer because it meant there was absolutely nothing I could have done differently to avoid it.

I had no control.

I remember asking, “So I could’ve been a chain-smoking alcoholic and had the same outcome?”

He didn’t quite know how to respond, but eventually said, “Your good health probably saved your life.”

He was right and for that, I am grateful.

A couple of months later, I ran into the on-call pharmacist who had been there the night I was admitted. She shared that she had prepared medications for seizures, strokes—anything that might have happened if my condition worsened. With tears welling in her eyes, she told me how relieved and overjoyed she was that none of it had been needed. She had read reports about the severity of my brain bleed and was amazed to see how well I was doing just eight weeks after surgery. She said such a rapid recovery, given how serious the situation had been, was both rare and miraculous.

Then she asked if she could share my recovery story with her colleagues, explaining that they rarely get to see or hear what happens to their patients after they are discharged from the hospital. They are often left wondering. That moment really stayed with me. I hadn’t realized just how deeply these healthcare providers care. The level of dedication and compassion I experienced at Riverside Hospital—from doctors and nurses to radiology techs and pharmacists—was truly extraordinary.

In the months that followed, their care stayed with me, even as my recovery unfolded in quieter, more private ways. If you have seen me in a ball cap this past year, or thought I had a “different haircut” or some “interesting bangs,” and wondered why, now you know. My hair is growing back. It was the only outward sign that something had happened. The rest was quieter, harder to see.

But even that physical sign told its own story. When my hair began to grow again, it came in drier, coarser, and more brittle, as if marked by trauma. There is even a faint wave running across it, marking the weeks I spent in the ICU, like the rings of a tree trunk recording its story, a reminder that my body had been focused on healing my brain injury before anything else.

I lost twelve pounds in just nineteen days. My appetite vanished, and everything I managed to eat tasted overwhelmingly salty. For some reason, I craved orange juice constantly. It was the only thing that hit the spot when nothing else appealed to me.

Loud noises felt like physical jolts, sharp and shocking, as if my whole body had forgotten how to absorb sound. I became hypersensitive to touch and sensations. High-pitched sounds or any sudden noise sent shivers through me, my nerves always braced for impact. Even the smallest sounds or movements would startle me.

I also began to feel claustrophobic at the slightest moment of intimacy — when someone’s face came too close, or when the air between us felt too heavy. What should have been comforting suddenly felt suffocating, as though closeness itself pressed against my chest and stole my breath.

And, ironically, for someone who is a dentist, I now cringe at the sound of saliva. The wet, clicking noises that never used to register now make my skin crawl. It is strange and disorienting to be so aware of things that were once invisible, to live inside a body constantly on alert for the ordinary.

Emotionally, I felt disconnected, unplugged. Even when I wanted to cry, I couldn’t. It took months before the tears finally came, and even now it is still a struggle. I felt like a stranger in my own body, trapped somewhere between recovery and remembering what it felt like to be myself.

What helped me cope? Protective denial. I didn’t even know there was a name for it until my therapist helped me through it. In those early months, I couldn’t fully accept what had happened, so I did the only thing I knew how to do: I kept moving. I “powered” through, pretending nothing serious had happened—like I hadn’t just undergone life-saving brain surgery.

I genuinely believed I’d be out of the ICU in under a week, so spending 19 days there left me frustrated—and left my husband stunned that I ever thought it would be a quick stay.

Throughout my entire career, I’ve only taken extended time off four times: for the births of my three children, and after the sudden death of my first husband. Looking back, my sense of reality was completely disconnected from what I’d actually been through. Despite everything, I threw myself back into work, traveled for continuing education, and convinced myself everything was fine. “Business as usual,” I told myself.

Much to the dismay of my husband and my team at the office, I stubbornly refused to slow down or take no for an answer. To me, rest was optional. Everyone around me worried about how active I stayed, but I kept insisting I was fine. I just needed to keep moving, because stopping meant facing the truth—and I wasn’t ready for that.

It never dawned on me that there could be a world where I couldn’t do something. The idea that I might not be able to practice dentistry, that my hands or my mind might fail me, simply never crossed my mind. It never occurred to me that I could lose the most basic functions, like walking, talking, or even holding a glass of water steady. Those are things you never imagine questioning until they are suddenly in doubt.

It was not denial as much as survival. I needed to believe I was still capable, still whole, still me — not just the dentist who ran a practice, but the mother who drove her kids to activities, made dinner, helped with homework, and tucked them in at night. I needed to believe I could still be part of their everyday world.

Other moms, who were also dentists, rallied around me. They created a meal chain for my husband and kids, sent daily texts of encouragement, and lifted me up in ways I didn’t even know I needed.

My office team went above and beyond to ease my transition back to work. They showed up, even when their own livelihoods were uncertain. They didn’t quit. They didn’t back away when things got hard. They stayed. And in doing so, they carried me through one of the hardest times of my life. Their loyalty and steadiness were deeply moving, something I will never forget.

I often talk with colleagues about how rare it is to find your ‘work unicorns’—those teammates who just get it, who carry both skill and heart, who make you better simply by standing alongside you. I was lucky enough to be surrounded by four unicorns when this happened, and the timing wasn’t lost on me. People like that don’t come into your life by accident; they’re a gift. And I will always be grateful.

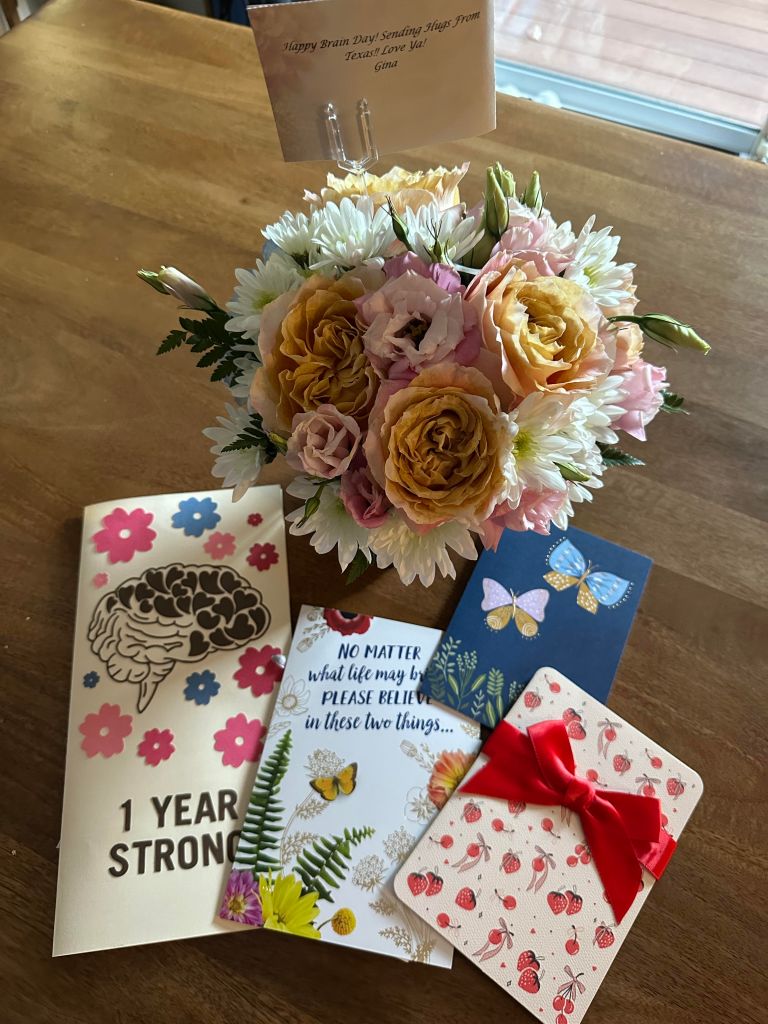

A year later, they surprised me by celebrating my first “Aneurversary” with heartfelt notes about their own feelings and how they had processed the ordeal. Reading their words moved me deeply. You don’t always realize the impact you have on people through your everyday interactions, until something like this reminds you how much we are all connected.

That same spirit of care surrounded me at home, too. My parents, my mother-in-law, and our babysitter stepped in to help with my kids. They didn’t hesitate—they just showed up, over and over again. Whether it was picking up from school, making meals, or simply being a calming presence. They filled in the gaps with love and steadiness. Their support gave us a sense of normalcy during all the chaos, and I’ll never stop being thankful for that. Knowing my children were cared for and surrounded by people who loved them gave me space to focus on healing.

And then, there’s my husband, my beloved Timothy. He truly lived our vows—in sickness and in health. His love and support never wavered, even when I was at my lowest. I absolutely believe he is my angel on earth.

I believe people come into your life for a reason, often coming at just the right moment without knowing how deeply they’ll impact you. Looking back, I see that everywhere, especially in those who stood by me during my darkest days.

Unfortunately, not everyone responded with kindness or understanding. I used to believe that if you showed up for others, they’d do the same. But nothing reveals the true nature of a relationship quite like a crisis. When I was unexpectedly hospitalized, I was forced to confront not just the fragility of my health, but of certain relationships. One of the hardest truths I faced was that empathy isn’t always mutual. I’ve always tried to lead with compassion and give others the benefit of the doubt, but while I was fighting for my life in the ICU, that same grace wasn’t always given to me.

Some patients complained that my absence was an inconvenience, even going so far as to leave negative reviews on Google—reviews that weren’t even accurate. That phrase, “family emergency,” was meant to protect my privacy and maintain some semblance of boundaries, but it should have been enough. I was in the midst of something life-changing and trying to survive one of the most difficult chapters of my life. Given that I do not have a history of taking extended time off, that phrase alone should have signaled that something serious was happening. Yet I still felt the crushing weight of responsibility for everyone else. I was fighting to recover, both physically and emotionally, while also absorbing criticism from people who had no idea what I was going through. It was isolating, and it made an already painful experience feel even heavier.

What hurt the most was not the risk to my reputation. It was the realization of how quickly some people demanded my constant availability, regardless of what I was enduring. Being seen as neglectful, when I was doing everything I could just to stay alive, left me bitter and disillusioned. I take my responsibilities seriously, often to my own detriment. In hindsight, I realize I should have focused on healing, not on trying to appease those who showed no concern for my well-being.

Even more disheartening were those who shared details of my situation without my or my husband’s consent—speaking openly when we weren’t ready to share yet. While my outcome was still uncertain, we were trying to protect our privacy and process everything in real time. Yet some chose to tell my story anyway, casting themselves as supportive or heartbroken, without ever reaching out to me directly. Their silence in private, contrasted with their public performance, felt hollow and made me question whether their concern was ever truly about me at all.

It was a sobering reminder that crisis doesn’t just reveal your character, it reveals everyone else’s too. And while some responses hurt deeply, they only made me more grateful for the people who showed up with genuine compassion, consistency, and quiet strength. Those are the people who really matter.

There are certain moments I carry deep gratitude for. I would never wish for this to happen, but somehow, everything aligned just enough for me to make a full recovery. I’m grateful I wasn’t traveling or working on a patient when the brain injury occurred. I’m grateful I didn’t lose consciousness and was able to make calls and text. I’m grateful a friend with medical experience urged me to go to the ER—and another was there to drive me immediately when I could barely see or move. I’m grateful my husband and kids didn’t have to find me in that terrifying state at home. I’m grateful for modern medicine, and for the doctors, nurses, and healthcare workers who treated me with such skill and patience. And most of all, I’m grateful for the incredible support that surrounded us—friends, family, colleagues—who quietly helped hold my world together.

It is not lost on me how quickly life can change. Just two weeks before my brain injury, I was smiling in a photo — healthy, full of plans, completely unaware of how close everything was about to change.

Shattering moments don’t care how fit you are, how many degrees you’ve earned, or how successful you’ve become. They don’t ask permission. Illness and crisis are great equalizers. They don’t discriminate and no amount of planning, preparation, or privilege makes you immune.

I’ve been through a lot in my 46 years. At 34, I was widowed in an instant and became a single mother to two very young children under the age of 3. I know what it means to wake up with your entire world changed, to summon strength you didn’t know you had—not just for yourself, but for the people who depend on you to keep going. Death and grief are not new to me. Neither is rebuilding.

But facing your own mortality is different. It’s not about putting the pieces back together. It’s about confronting the terrifying reality that there might be nothing to return to. It forces a different kind of awakening. This time, I wasn’t just grieving what I had lost. I was fighting for the chance to still be here at all.

And more than anything, I was fighting for my kids and husband. The older two were so little when their father died, too young to hold real memories, just the faint impressions left behind in photos and stories I have told them. If I had passed away too, there would have been no one left who remembered their beginnings — the sound of their first laugh, the softness of their hair, their first word. It breaks my heart to think how easily those small, precious pieces of their story could have disappeared with me. Surviving means they still have someone who remembers, someone who can tell them who they were before the world became uncertain.

In a world obsessed with “more,” I’ve started to wonder what we’re actually gaining. We spend so much of life racing the clock, chasing success, comparing ourselves to others with more money, more recognition—“more” everything. We get caught up in carefully crafted images, thinking that if we just push a little harder, achieve a little more, it’ll finally feel like enough. But here’s the truth: no amount of success or wealth buys you time. And none of it makes you immune to what life can take away.

Coming face-to-face with death cuts through all the noise. It forces you to see what truly matters and what never really did. The constant pursuit of “more” often pulls your attention away from the people and moments that count the most.

I don’t pretend to be an expert on trauma or recovery. After being widowed and almost dying myself, I’ve learned that pain doesn’t make you an expert—it just humbles you.

When you think you’ve already been through hell, life finds new ways to remind you how fragile it all is. It strips away the sense of control and leaves you asking harder questions: How much time do I really have? What am I doing with it? What will my legacy be? It forces you to stop just going through the motions and start being present—because being alive isn’t promised. It’s a gift.

I spend my time differently now—not perfectly, not as some enlightened version of myself, but more deliberately. With less tolerance for what drains me, and more intention toward what and who restores my energy.

I no longer have the capacity to fake pleasantries or pretend everything is fine when it’s not. You might notice me stepping back from certain conversations, commitments, or situations—not because I care less, but because I’m learning to care more intentionally.

Health and peace of mind—physical, emotional, and mental—are not luxuries; they’re necessities. After coming so close to losing everything, I’ve learned to protect that peace firmly. I no longer have space for drama, performative compassion, or one-sided relationships.

I’ve also redefined what “forgiveness” means to me. The phrase “life is short, forgive quickly” is often used to excuse harmful behavior. But to me, forgiveness means letting go of those who don’t value you and refusing to give them endless opportunities to hurt you again and again.

This experience offered a painful but powerful truth: the ability to see people and situations for what they truly are, not what I hoped they would be. I’m not the dentist for everyone. I’m not the friend for everyone. I’m not the family for everyone. And that is okay. I still give my all, but now I protect my peace of mind with intention. There is a quiet freedom in that kind of clarity.

One year later, my scars are healing—some visible, most invisible—but they remind me every day that I’m still here. The doctor was right. I’m not the exact same person I was before this happened. But maybe that’s not a bad thing. This experience forced me to slow down, to feel more deeply, and to notice things I might have overlooked before. Life isn’t just about surviving—it’s about knowing you survived and choosing to live fully afterward.

Looking back, I’ve come to realize that gratitude and grief can coexist. Strength and vulnerability aren’t opposites—they’re partners. And healing isn’t always linear, but it is always possible.

So if you see me smiling a little more, hugging my kids a little tighter, or simply being more introspective, it’s because I’ve lived through the unimaginable and made it to the other side. I’m not untouched but undeniably alive. This experience has changed me, giving me a new perspective on what truly matters and a deeper understanding of how finite our time really is.

I wasn’t sure if I wanted to share this experience. At first it was hard to talk about what happened. I felt shocked, vulnerable, and at times even ashamed. Some of that shame came from believing I should have been stronger and from fearing others wouldn’t understand. I worried about being judged or pitied, and that fear kept me silent. I’m a private person, and opening up like this doesn’t come easily.

Still, I found a way to start. Writing it down has been unexpectedly therapeutic. Over time, it has helped me slowly piece together what happened, allowing me to process it in ways I couldn’t when everything still felt so raw. In some ways, the act of writing has become part of my healing—each word a small step toward understanding, and maybe even acceptance.

Through that process, I began to understand something important. You have to ignore the “why didn’t you…?” questions and the “you should have…” comments. No one can tell you how to grieve, or how they would have handled it. In those moments, no one really knows what they would do. You simply do what you can with what you have.

I have learned that grief is deeply personal. There is no single “right” way to move through it, and no one can tell you how it should look. People often mean well with advice or stories of what helped them, but the truth is that even those who have known loss cannot fully know yours.

Surviving something like a near death experience makes this even clearer. Grief is not only about losing someone else, it can be about almost losing yourself. It may bring sorrow for the life you once imagined, guilt for surviving, or a deeper compassion for others. However it comes, overwhelming one day and quiet the next, it is still valid. What matters is giving yourself permission to grieve in your own way, at your own pace.

That’s part of why I’m telling my story. I’m not sharing it for sympathy. I’m sharing it because sometimes, simply knowing someone else has made it through something painful can spark a small light of hope for the road ahead. You never really know what someone is carrying. Often, the people who look the strongest are holding the heaviest burdens. That’s why kindness matters so deeply—it isn’t just a nicety, it’s a necessity. A single act of patience, grace, or compassion can shift the weight someone carries, even if you never see the difference it makes.

So love hard. Laugh freely. Let go of what—and who—drains your soul. Show up for those who matter, and also for yourself. Life is short. Time is precious. Peace is priceless. And if you’re lucky enough to still be here, don’t just exist—live.

And for that, I’ll never stop being grateful.

✨ A Living Story ✨

This story reflects my current understanding and memories. Healing and remembering are ongoing processes — living things that shift and evolve with time. As I continue to recover, new details or insights may surface, and my perspective may deepen or change. I share this now with honesty and care, knowing that both memory and meaning will keep unfolding as life moves forward.